Canvas2Cuticles: an Aaron Douglas adorned manicure masterpiece

This new series is part beauty blog, part object lesson tracking the inspiration and design behind my latest nail set.

I would not call myself a beauty girl; as beautiful as I am, the makeup movement missed me. I have never worn a full face, know nothing of products or techniques, and recently had to be convinced that skin care is more than washing my face with water and a rag. While I’m now dipping my fingers in cleansers, salves, and moisturizers, wearing sunscreen daily has not yet transformed me into a made-up lady. Thankfully, no makeup makeup is in, and natural beauty is forever a trend. All of this to say, I may not be a beauty blogger, but I do know a thing or two about presenting polished. In this vain, I welcome you to my latest column, Canvas to Cuticles.

For me, a manicure is all of the adornment I need. Inspired by my stylish Spelman sisters, it is the beauty bandwagon I hopped on toward the end of college. Starting with medium-length square French tip acrylics and working my way to longer, more complex coffin-shaped designs, I’ve experimented with healthy (Gel X) applications for my paper-thin and short as a stump natural nails. After years of anxiously biting any bit of white that grows as I care for my cuticles and watch my nails reach new lengths, a regular mani-pedi routine has become my favorite self-care practice. Last month, I ventured into new territory to accessorize my tendency to talk with my hands with a nail design of my dreams, inspired by Black History Month and the resurgence of attention on the Harlem Renaissance.

When my friend, emerging art historian Neil Grasty, reposted two Aaron Douglas paintings from ArtNoir on his IG story, I was immediately struck with the idea of a nail set. I downloaded a template from Etsy and designed a miniature manicure masterpiece, pulling elements from Douglas’s compositions to craft a set of claws that evoked the same energy. On the right hand was a proverbial mountain top of modernity, and on the left was a monochromatic cotton club set with a dancer and her band. When I sent Neil the rendering and asked for his blessings, he was confused, immediately accusing me of blasphemy; what had I done to Douglas? I was scared that my interpretation was in poor taste, like the folks who try to pimp public domain artworks at Target and on the commercial market. But a bit of explanation, or rather an object lesson on what he was looking at, reassured Neil and cosigned my design. Having the vision is one thing, but like an artist whose practice involves studio assistants, I needed help bringing my idea to life. I rifled through Instagram tags, looking for nail techs in Chicago who could push paint, do character work and enjoy creative ideas.

Reyna Did My Nails in her Pilsen studio. She laid out small drops of purple, pink, and yellow polish on a crystal palette. Each brush break to dip a single finger into the pool of curing blue light had me squealing with excitement. Her tiny microscopic brush built layer upon layer of radiating color and revealed two Aaron Douglas compositions. Watching the process, I wondered how similar Reyna’s technique was to that of the Kansas-born painter, whose career took off in the 20s as he attempted to redefine Black representation in the arts through an approach to modernism that relied heavily on geometry and silhouettes, refreshing European cubism with a FUBU mindset. His style became the calling card of the Harlem Renaissance, then termed the New Negro Movement, and was influenced by the theories of Alaine Locke and literature of the time, including FIRE!! and Crisis magazines, for which Douglas designed the cover art. I got to tell Reyna all of this history as she questioned the inspiration behind my set, saying folks don’t typically request such original designs. I was happily challenging her skillset. Rise to the challenge she did; by the end of our session, my blues woman was dancing between the palm fronds, and I had the whole world on the tip of my finger, a globe related to Douglas’s interest in exploration and travel decorated my thumbnail in a pretty pink palette.

For the next three weeks, I obsessively fawned over my fingers. I educated anyone who listened or even slightly complimented my set on the significance of the artist I chose to honor. A combination of personal research and timely art world discourse brought Aaron Douglas to the fore, not just on my fingertips. At the Atlanta Renaissance, Now! Symposium, which celebrated five years of the AUC Art Collective, I sat in on a keynote by Dr. Denise Murrell, Curator of The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, the blockbuster exhibition now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Murrell introduced her curatorial vision by harkening on the importance of HBCU Art Collections in supporting and preserving the legacies of African American artists such as Douglas, Archibald Motley, William H. Johnson, and Laura Wheeler Warring. Featuring over 160 works, the Met’s exhibition is organized into four parts: tracking Black portraiture, Renaissance literature, transatlantic cultural exchange, and the nightlife culture.

Further context came through the exhibition’s accompanying podcast, Harlem is Everywhere, hosted by my friend, cultural writer, and critic, Jessica Lynne. The podcast revolutionizes artistic interpretation of scholarly work, bringing expert voices such as Richard J. Powell, Bridget R. Cooks, and Spelman’s own Mary Schmidt Campbell together with a captivating soundscape that evokes the hustle, bustle, and vibe of early Harlem, offering imagery you can easily imagine yourself a part of. Episode 1, The New Negro, has a segment on Douglas’ prolific contributions to the culture.

Additional sources that rounded out my object lesson on Douglas came from my library pickup, the 2007 catalog of Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist from Yale University Press in association with the Spencer Museum of Art. This catalog features many works from the Met exhibition, laying the context around Douglas’s career from the POV of practicing artists and scholars, including the late David C. Driskell, Douglas’ mentee, and predecessor as Chair of Fisk’s Art Department. While I originally checked out the book for photoshoot purposes, stuck on the serendipity of the cover art being the same image I selected for my nails reinforced the aspiration of Canvas to Cuticles.

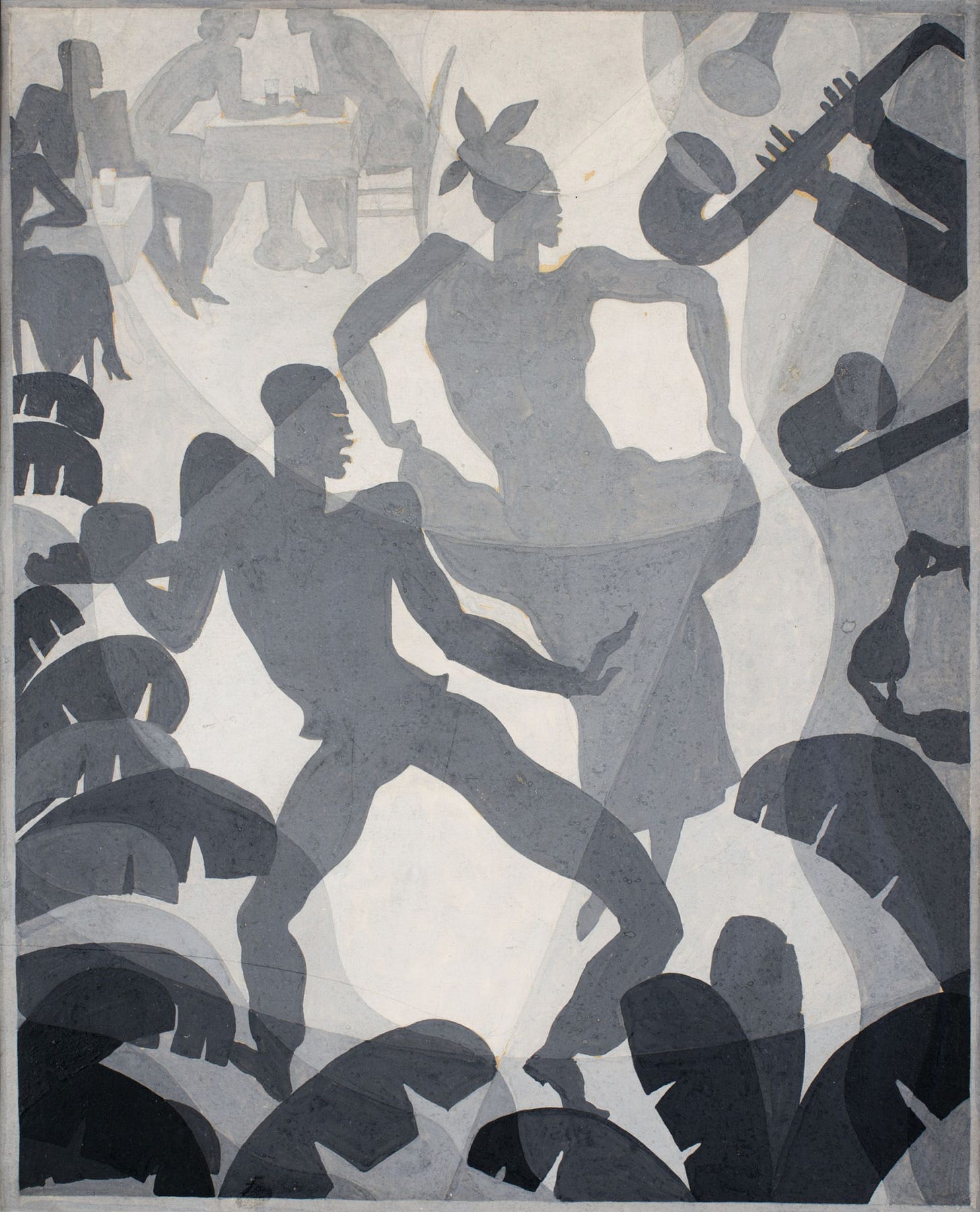

Aaron Douglas’ oil paintings Dance (1930) and Aspiration (1936) decorate my left and right hand, respectively. The monochromatic club scene features a blues woman and a dancing man with a top hat at its center. The band and club crowd at its borders join a jungle of palm leaves, harkening to the primordial origins of Black dance traditions. “Douglas called the Lindy Hop ‘remarkable,’ writing that it ‘was not created by a single dancer nor a couple working in isolation, but was rather a kind of instant miracle of poetic movement achieved like many other Negro dances through efforts of many dances humbly striving to harmonize, to synchronize into a perfect form the various movements of man, bird and beasts, always struggling, often unconsciously, to reflect to interpret the black man’s notions of life, joy, and oneness with all of God’s created things” (Harlem, Modernism, and Beyond, 23). Author Susan Earle describes in this essay that “Douglas’s positive depiction of women was in line with his experience in Harlem, where a powerful array of female writers, dancers, poets, and singers fashioned key aspects of the era, including its charged urbanity and modernity” (20). Combining these sentiments settles my heart in thinking Douglas would not only approve but would love my translation of his artwork into a representation of my femininity.

I am also struck by Douglas’s poetic offering, the lyricism of his language, and the themes of faith I initially failed to recognize. In his catalog essay on memories of his mentor, David C. Driskell quotes the artist describing one of his signature design motifs, gradient concentric circles radiating out in his images. Saying, “He noted that the color gradients of light and shadow in his art evoke the call and response of a Black congregation echoing the truth of the preacher’s sermon” (91). Of Aspiration, Renée Ater writes on the ray of light “signif[ying] divine inspiration or the light of Christianity … signal[ing] the North Star or a radiating star of emancipation” (107). Understanding the artist’s spiritual beliefs, I am even more aware of how my nail art is a vehicle for arts education and spreading God’s word.

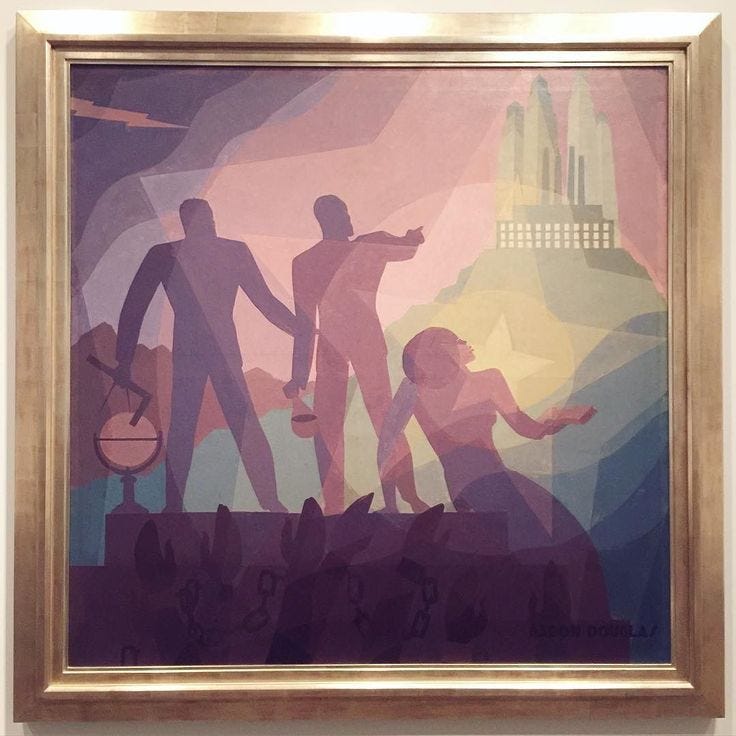

The North Star symbolism might be an ideal across Douglas’s narrative paintings, but in Aspiration, the 1936 movable mural created for The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition held in Dallas that year, the star imagery more likely references the Lone Star of Texas. This painting is one of Douglas’ most popular and is just one of two still existing panels from a four-part narrative mural that welcomed Black visitors into the segregated fairground hall. Douglas’s presence at the Centennial was thanks to a Harmon Foundation commission, patrons who supported the artist for many decades. The entryway work, meant to honor African American presence in the state, was advocated for by the local Black community who had to lobby with policymakers and privately funded an exposition space after Texas Centennial organizers failed to include African American presence in the dominant history of their state, and it’s 1836 declaration ending Mexican rule in the region.

In her essay, “Creating A ‘Usable Past’ and A ‘Future Perfect Society’: Aaron Douglas’s Murals for the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition,” Ater describes Douglas’s use of a “useable past” and the critical fabulation (a la Saidiya Hartman) required to imagine and retell an African American history often minimized or misrepresented. The painting features three of Douglas’s signature silhouetted figures, two men and one woman, crown on a pedestal where chained and enslaved hands of the past reach up towards freedom. The central figures each yield an instrument of learning, including the seated woman holding a book, the man to the left holding a compass and carpenter’s square signifying architecture, and the central man, a beaker in his left hand, pointing to the proverbial city on the hill with his extended right arm. This figure graced my ring finger. Douglas’s mural created a visual language to tell the history of the past and the future of modernity. The Hall of Negro Life opened on Juneteenth, 1936, signaling Black freedom in the state of Texas and raising respect for the race nationwide.

My nails grew out, but I’ll never grow tired of Aaron Douglas. I sadly soaked off the set last week but have been transformed by the tantalizing energy and cultural ideals of the New Negro Movement. A Renaissance is among us; recent articles, The Dinner Party That Started the Harlem Renaissance and The Women Who Run Harlem, offer both historical and future-looking perspectives on the movement.

Absolutely loved this article Ming! I’m glad to have been the inspiration for this glorious nail set